Our Nation's Capital's Historic German-American Cemetery

Established 1858

- Amelia Erbach

- August Gottlieb Schoenborn

- Julius Frederick Viedt

- Friedrich W. Imhof

- (Sophus) Emil Friedrich

- Louis Schade

- William A. Peterson

- Charles Shambaugh

- Joseph Peter Gerhardt

- “Move up Joe” John Joseph Gerhardt by Gary (Gerhardt) Carl Grassl

- W. Henry Walther

- Henry Xander

- Others

In 19th century Washington, DC, few German immigrants became rich and famous. Those who did usually chose to be buried in a more upscale cemetery. Yet Prospect Hill did become the final resting place for many who contributed significantly to the growth of the city and the German community. These persons include:

Pioneer Woman Physician

On May 2, 1884, she had graduated from the Washington Training School of Nurses located in the Old Souls Church at 6th and D Streets, NW. In 1889 she had received the degree Doctor of Medicine from the medical school of Columbian University at 15th and L Streets, NW, which had begun admitting its first women. (Columbian University became The George Washington University in 1904.) In 1900 her medical office was on Capitol Hill at 21 3rd Street, NE; she specialized in the illnesses of women and children. In 1901, Dr. Erbach served on the Medical Society's Committee on Public Health. Dr. Erbach died on May 3, 1941, in Washington, D.C., at the age 80. She was buried in Prospect Hill Cemetery in lot C-6-8 (Charles Erbach lot owner).

Her father was Charles Fairfax Erbach, born in Saxe-Weimar, December 1, 1826; immigrated in 1852 aboard the S.S. Hopewell; occupation brewer (1870 census); affiliated with Concordia Church; died at 1338 Maryland Avenue, NE, Washington, DC, on October 10, 1881, at the age of 54 years 10 months 18 days; (Charles Erbach, lot owner; C-6-7); funeral listed in Concordia Church records.

Her mother was Mary (Marie) C. Bauer, born in Bavaria ca. 1828; lived at 1330 Maryland Avenue, NE (1880 census); died in July 1908 at 709 East Capitol Street, DC; 80 years of age (Charles Erbach, lot owner; C-6-6).

History of the Medical Society of the District of Columbia, 1817- 1909, by John B. Nichols, Committee on History, Washington, D.C. 1909, pp. 119-120.

back to top

In 1849 Schoenborn immigrated to the United States, arriving in New York in November of that year. From there he traveled by canal to Wisconsin, but found it afforded no employment for me except as a mason, plasterer, painter and farmer.

Two years later he left for Washington, DC, traveling by canal and stage as far as Cumberland, Maryland, and from there to Washington by rail. He arrived here in May 1851.

By the following month he had found employment in the Office of the Architect of the Capitol under Thomas A. Walter, and was soon making all the original drawings for this office. He had the highest regard for Walter s skills, and noted that Walter treated me as his son.

On December 24, 1851, the old wooden Library of Congress became engulfed in flames. It was early in the day, and as I was boarding nearby, I hurried to the fire and helped to save as many books as possible. In April 1852 we commenced the rebuilding of the present iron Library.

In the following years Schoenborn made architectural drawings for Montgomery Meigs, including ones for the Washington aqueduct, which would provide parts of the city with safe water.

In March 1855, the old wooden dome of the Capitol was taken down. Schoenborn made the original drawings for the new iron structure. He noted that although Mr. Walter was a first-rate architect and a good draughtsman, he had little experience in iron construction. Thus it was that Schoenborn's design for the dome s skeleton was chosen and subsequently adopted as the only feasible one...by which the interior architecture could be properly developed.

In 1861, at the beginning of the Civil War, the Office of the Architect of the Capitol was closed for nine months. During that time Schoenborn spent time drawing maps for General McDowell, and then drawing plans for forts, barracks, hospitals and other temporary buildings for the Quartermaster General s Office. In May 1862, Walter notified Schoenborn to return to the Capitol.

It was in November 1864 that the new dome was finished and the headpiece of the bronze Statue of Freedom was lifted in place. Mr. Walter requested me to go and represent him, and so I and my brother William were the only ones who stood up there some distance above the [statue s] head to witness the crowning ceremony amidst the firing for 35 guns from the surrounding forts. It was Schoenborn who placed a dedicatory wreath at the foot of Freedom.

Walter resigned in fall 1864. Schoenborn noted that during the 13 years I spent with Mr. Walter I have learned a great deal from him, as he was not only an architect, but also an excellent draughtsman and a good watercolorist. His father was a bricklayer and of German descent.

Walter's replacement was Edward Clark, whose abilities Schoenborn felt were far below those of Walter. Unlike Walter, Clark's love was politics. ...He is a smart lobbyist before Congress, always spending most of his time in this capacity, and this is all.

Some of the works Schoenborn planned, drew and executed include the Monument of the Un known Soldier and main gates at Arlington National Cemetery; E Street Baptist Church; Corcoran's Mausoleum at Oak Hill Cemetery; wings of the Patent Office Building; portions of Congressional Library; extensions of the Treasury, Post Office Department and DC Reform School buildings; repairs and alterations to the Smithsonian Institution; many buildings at the National Soldiers Home; engine house and Senate stables; two complete plans for the new Government Printing Office; the Medical Museum; two wings of Providence Hospital; additions for Columbia Hospital; and quite a number of private houses, including those for Senators Morrill, Edmunds and Sherman. He designed the original gatehouse at Prospect Hill Cemetery, as well as his own gravestone. In addition to his home at D Street, he designed and had built two town houses on East Capitol Street which still stand and are inhabited today.

Schoenborn married Helen Klee on December 10, 1851. She was a native of Heubach, Hesse, born there on March 9, 1828. Together they had 9 children.

Schoenborn remained with the Office of the Architect of the Capitol until the time of his death on January 24, 1902. His wife died two years later, on January 30, 1904.

[The quoted material in this article come from one of Schoenborn's journals, dated August 21, 1895, recently donated to the Office of the Architect of the Capitol by his descendants.]

back to top

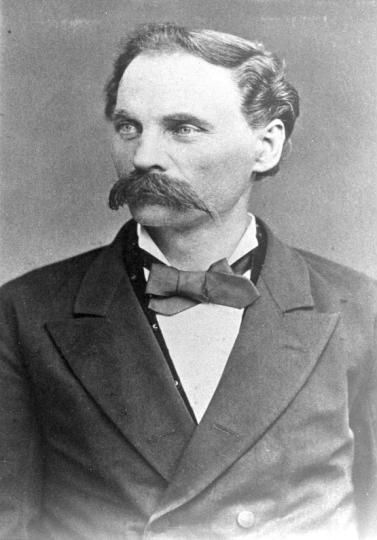

Julius Viedt was born in Braunschweig on April 8, 1822, the son of

Johann Christoph Viedt, born in Kutasse on January 12, 1778, and

Dorothe Ilse Viedt, born in 1783.

Julius Viedt was born in Braunschweig on April 8, 1822, the son of

Johann Christoph Viedt, born in Kutasse on January 12, 1778, and

Dorothe Ilse Viedt, born in 1783.At age 26 Julius sailed from Hamburg, entering the United States at New York City on October 8, 1848. Six months later, on April 13, 1849, in New York City, he married Fredericke Duhring, a native of Hamburg

Shortly after their marriage the couple moved to Washington, DC. Establishing their home at 121 D Street north (the before-1870 Washington numbering system), they both worked diligently to sustain themselves, Viedt as a cabinetmaker and his wife as a dressmaker. Throughout his life, Viedt remained a skilled cabinetmaker.

The couple had four children Henrietta Hermina; Julius, Jr.; Flora; and Amelia who survived childhood. (At the time of the 1900 census, Fredericke Viedt indicated she had given birth to 13 children.)

Viedt applied for naturalization on July 6, 1854, and became a citizen of the United States on December 31, 1856. During the Civil War he joined the Union Army, serving in Company K, 1st Infantry, Maryland Regiment, where he attained the rank of second lieutenant.

At age 73, on January 8, 1893, Viedt died at home of tuberculosis.

His Washington Journal obituary, printed on January 17, 1893,

stated: 'On Tuesday, the coldest day that we had here in Washington

since 1881, the Sängerbund members sang a funeral dirge in front

of the tomb in Prospect Hill Cemetery for the oldest active

member, Julius Viedt, 72. Another funeral hymn they had sung before

in the house where he died, 121 D Street, NW. Pastor Drewitz preached

a funeral sermon in the home and read the interment service at the

grave...'.

At age 73, on January 8, 1893, Viedt died at home of tuberculosis.

His Washington Journal obituary, printed on January 17, 1893,

stated: 'On Tuesday, the coldest day that we had here in Washington

since 1881, the Sängerbund members sang a funeral dirge in front

of the tomb in Prospect Hill Cemetery for the oldest active

member, Julius Viedt, 72. Another funeral hymn they had sung before

in the house where he died, 121 D Street, NW. Pastor Drewitz preached

a funeral sermon in the home and read the interment service at the

grave...'.Fredericke Viedt died on March 31, 1906, at age 77.

On Memorial Day 2012, Monday May 28, the Washington Sängerbund dedicated a new grave marker to honor Julius Viedt as its first president in 1851.

back to top

One of the first things he did upon coming to Washington was to join Concordia Church. He had been a member there for only one year when he founded the church's Sunday School, serving as its superintendent for 30 years during the ministries of Pastors Finkel, Rietz, Kratt, Schneider, Miller, Drewitz and Menzel. He also served as president of the church council for 20 years.

It was the dream of Pastor Kratt that our city should have a German orphanage. It was Imhof whose warm German heart drove him to energetically engage in this project and serve as Pastor Kratt's right hand in acquiring property for the orphanage. Once it was built, Imhof continued to work for its welfare, serving many years on its Board of Trustees, including four years as vice president and ten years as president of the Board.

Imhof married three times. His first wife, the former Carolina Schneider, apparently died in child birth and was buried with her child on February 15, 1870. His second wife, died ten years later. His third wife, Pauline, was buried in April 1898. He had six daughters who reached adult hood, and one son, rederick W. He also had three children who died young. However, it was the sudden death of his son Frederick who died in November 1904, when the youth came in contact with an electric wire and was instantly killed, [that] was definitely the heaviest blow...that he, in his long life, suffered. Son Frederick, age 16, was trying to help a horse who had become entangled in live electric wires that fell during a storm.

For 25 years Imhof served on Prospect Hill's Board of Trustees.

At age 87, Imhof died in the home of one of his daughters on April 26, 1916. On the anniversary of his birth, April 29, after his funeral service at Concordia, the mourners processed from the church to Prospect Hill. Speaking for the Board of Directors of the orphanage, president Martin Wiegand read a proclamation, which concluded 'Furthermore it is concluded that Mr. Friedrich Imhof was in every relationship a model citizen and worked throughout his life for the welfare of the orphans; that the Board of Directors of the German Orphanage bring our condolences to the family of our late friend along with a copy of these resolutions; and that these resolutions be incorporated in our record and become in the Washington Journal a testimony of the regard with which we honor our friend and colleague.' Other participants in his burial ceremony included representatives from the trustees of Prospect Hill, members of the Concordia church council, and members of the Knights of Pythias.

The children of the German Orphanage adorned the grave of Papa Imhof with flowers. Washington's German-American community had lost a great man.

back to top

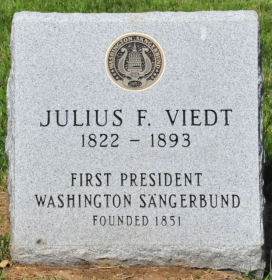

On September 13, 1852, at Concordia Church, Friedrich married Caroline Maria A. Gebhardt. Caroline was born in Germany November 10, 1825. During the first years of their marriage the couple buried three children in the Old H Street Cemetery, whose remains were transferred to Prospect Hill on December 2, 1859.

During the 1850s, Friedrich was employed as an architectural draftsman by Robert Mills. By the time of the 1860 census, he and Caroline had two sons, Leon, 3, and Albert, 1.

|

|

grave plaque source: findagrave.com |

By 1870 Friedrich had his own practice as an architect. Among his works were two neighboring row houses at 321 and 323 East Capitol Street; he made house number 323 his home for the rest of his life. Next door to these two houses are a pair of townhouses designed by August Schoenborn. All four houses still stand, in excellent condition.

On September 19, 1886, Emil Friedrich, age 58, died at home. His wife Caroline died there ten months later, on July 15, 1887.

back to top

When the 1848 revolution began, Schade was a law student at the University of Berlin. Along with other students, he became involved and was condemned to death as penalty for helping erect barriers in the streets of Berlin against government troops. He escaped and came to the US in 1851. After a few months in New Jersey, he came to Washington.

Schade could speak 4 languages and translate with ease 5 others. Initially he secured a position at the Smithsonian Institution as assistant librarian. In 1854, he transferred to the Census Bureau.

A year later Schade became a translator and statistician for the State Department. There he was noticed by Senator Stephen Douglas, who in 1856 induced Schade to go to Chicago as editor of Douglas's German-language "National Demokrat," and English "National Union." Thus Schade became involved with the Democratic Party as a supporter of Douglas, whom he helped campaign against Lincoln in 1860. When Douglas was defeated, Schade returned to Washington and opened his own law practice. At the end of the Civil War, he undertook the extremely unpopular position of becoming the defending attorney for Swiss-born doctor Capt. Henry Wirz, superintendent of the Anderson, Georgia, military prison, who had been accused of killing Northern soldiers. Believing that justice demanded that all citizens be given a fair trial, and coming to believe that Wirz was being unjustly accused in order to implicate Jefferson Davis, with his career at stake Schade represented Wirz before a military commission. Wirz was convicted and executed November 10, 1865, and was carelessly buried in the Washington prison courtyard next to Mrs. Surratt. When Schade was finally allowed to give Wirz a Christian burial, he moved the remains to Mt. Olivet Cemetery.

Schade later let it be known that Wirz had been offered a stay of execution if he would implicate Jefferson Davis as a conspirator. Wirz replied that he knew nothing about Jefferson Davis and would say nothing against him, even to save his own life. Schade spent the rest of his life trying to clear Wirz's name.

In 1867, after publishing his now-famous letter to the American public in which he told his version of the real happenings at Andersonville, Schade returned to Europe to check on the welfare of Wirz's family. While in Stettin, Prussia, on September 18, he married Anna Krieger, who returned with him to the United States. Together they had 6 children. The family were members of Concordia Church.

In 1870, with the help of prominent Washington citizen W. W. Corcoran, Schade established The Washington Sentinel, which he published for 30 years.

When Schade learned, in 1879, that speculators wanted to buy the house in which Lincoln died, Schade purchased it himself, living there and publishing his newspaper until 1896, when he sold his home to the DC Memorial Association to be used as a memorial to the assassinated Lincoln.

Schade died February 27, 1903, at age 73. His wife, 69, died on April 22,1912.

back to top

|

|

on 10th St, NW source: Wikipedia |

In 1849, Petersen constructed a red brick three-story-with-basement townhouse on 10th Street, opposite Ford Theater. A merchant tailor, he had his shop around the corner at 11th and Pennsylvania Avenue and, as did many 19th-century Washingtonians, he also rented out rooms in his home to transients and new immigrants. It was to Petersen's home that Abraham Lincoln was taken after being shot on April 14, 1865, and where he died early the next morning. Julius Ulke, a German-American photographer who was boarding with Petersen at the time, took the historic photograph showing the room a few minutes after President Lincoln's body was removed from the bedroom.

Petersen died on June 18,1871, at age 58 years. His wife died exactiy 4 months later.

back to top

On June 10, 1861, he enlisted in the Pennsylvania Reserves, where he served as a corporal in the infantry. On August 30, 1862, he was wounded; six weeks later, on October 13, 1862, he left the service on a disability discharge.

Four years later, on July 17,1866, he was awarded a Medal of Honor for his meritorious actions at Charles City Crossroads, Virginia, June 30, 1862. The citation was "capture of flag."

It appears that Shambaugh returned to Pennsylvania after his discharge, for it is known that a daughter, Jennie, was born to him there in 1873. Another daughter, Lizzie, was born in Kansas in 1877. (We know nothing about his wife, who apparently was deceased by the time the 1900 census was taken.)

By 1890 he had come to the District of Columbia and was living at 6121 Street, NE. According to the City Directories for 1890 and 1891, in 1890 he was employed as a watchman; in 1891 he worked as an elevator operator. By 1900 he had moved to 1108 K Street, NE.

He died October 12, 1913, in Hyattsville, Maryland, at age 73.

back to top

|

| source: The National Republican, Washington, D.C., August 29, 1881 |

Employed as a merchant and innkeeper in Bonn, on October 15, 1842, Gerhardt married 19-year-old Ernestine Leonard. Together they had 4 children.

During the 1848 revolution in Baden, Gerhardt took a prominent part with Carl Schurz, G. Kenkel and H. Rasler, commanding a battalion of volunteers in the Bodisk insurrection. Imprisoned in the Rastatt fortress, he managed to escape, fleeing to Switzerland. In 1850 he immigrated without his family to the United States. After a brief stay in New York City, he came to Washington, DC. In 1853, in Baltimore, Maryland, he married German immigrant Dorothea Wolff. Between 1853 and 1871, the couple had nine children.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Gerhardt organized a Turner Company, leadership of which gave him the rank of captain. Some of his descendants recall being told that early in the war, Gerhardt was in charge of protecting the old Union Station. In summer 1861, Gerhardt was asked to go to New York to lead the 46th New York Volunteers. Beginning there as a major, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel in September 1861, and to full colonel in January 1863. He participated in military operations in Cincinnati, Vicksburg and Petersburg, and was wounded several times.

In Vicksburg, Gerhardt contracted malarial fever; he also had asthma and complications from his war wounds. On August 15, 1863, he resigned from the Union Army because of ill health, and returned to his hotel and restaurant business in Washington. He was a well-known restaurant- keeper, his last place of business being on Sixth street, adjoining the Washington Gymnasium. He was breveted Brigadier General by Lincoln for gallant and meritorious service during the Civil War.

Gerhardt's descendants believe that a friendship developed between Joseph Gerhardt and President Lincoln. Oral legend indicates Gerhardt may have visited the dying President at Petersen House (quite close to the Gerhardt Hotel), although this legend has not been proven. It is known that Gerhardt named one of his sons Abraham Lincoln Gerhardt following a formal request to President Lincoln to do so, as was the custom at that time.

General "Joe" Gerhardt died at his home, 1626 14th Street, NW, on August 19, 1881. He was 66 years old.

back to top

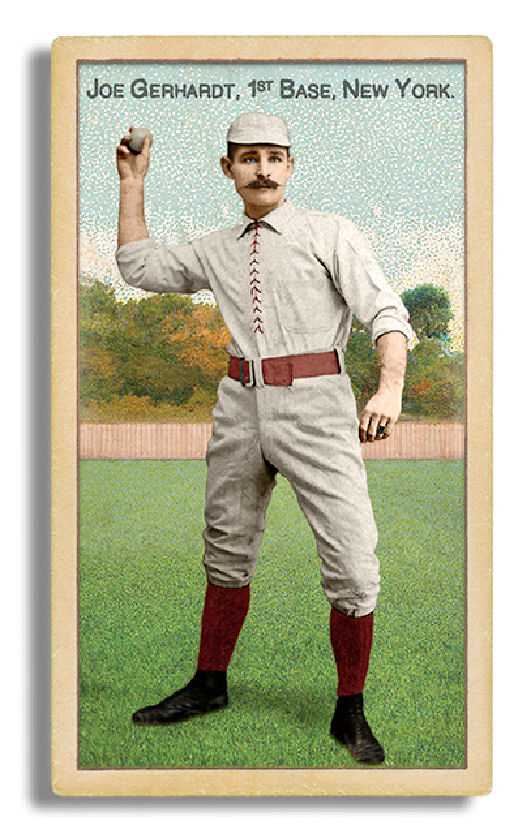

Born February 14, 1855, in the District of Columbia, John Joseph

Gerhardt was the eldest son of Civil War General Joseph Peter

Gerhardt and of Dorothea Wolff, both immigrants from Germany. As

Captain Gerhardt, he commanded German-American troops in the defense

of the Nation's Capital at the outbreak of the War of the Rebellion

in 1861. After the District of Columbia was secured, he helped

organize the 46th Regiment of New York Volunteer Infantry.

Born February 14, 1855, in the District of Columbia, John Joseph

Gerhardt was the eldest son of Civil War General Joseph Peter

Gerhardt and of Dorothea Wolff, both immigrants from Germany. As

Captain Gerhardt, he commanded German-American troops in the defense

of the Nation's Capital at the outbreak of the War of the Rebellion

in 1861. After the District of Columbia was secured, he helped

organize the 46th Regiment of New York Volunteer Infantry.His son John Joseph was born in the family home on Maryland Avenue, SW, practically in the shadow of the U.S. Capitol. The Gerhardt home stood opposite the U.S. Botanic Garden where Maryland Avenue stops on the west side of the Capitol grounds. At that time dwellings crowded close to the Capitol building. This area is today part of the National Mall.

John Joseph, who went by the name of Joe, was about 6 years old when his father went to war. Did Joe know German besides English? Since his parents were native German speakers, this was undoubtedly the language of the home; therefore, Joe understood German. He learned the rudiments of the national pastime in the backyard of the White House known today as the Ellipse. He was nicknamed "Move Up Joe" for his habit of urging base runners to advance to scoring positions.

The development and growth of our national pastime is closely intertwined with the Civil War. Soldiers played the game in their camps and spread it around the nation. That the eldest son became a professional baseball player speaks to the Americanization of the Gerhardt family. Immigrants generally find the game boring, because they do not understand the intricacies and the strategies involved. Big league baseball requires as much calculation as chess; it is a thinking person's game. Unfortunately it is no longer the nation's primary pastime; less demanding sports have taken its place.

"Move Up Joe" was almost 6 feet tall, weighed 160 pounds, batted and threw right handed. He played as a major league infielder from age 18 to 36 during the last quarter of the 19th century, the beginning of professional baseball. From 1873 to 1891 Gerhardt played for 13 different major league teams during 16 seasons. On three occasions he was player manager of major league teams. He also guided minor league outfits to three championships. He played for the Nationals of Washington when they won the playoff series between the two major baseball leagues.

Gerhardt played a form of baseball that would have appeared strange to us. Wrote Michael Coffey, "pitchers threw from a flat, squared off area, like a box…. They'd only recently started throwing overhand, underhand delivery being the rule till the mid-1880s. The front of the pitcher's box was 50 feet from home plate, which itself was square and not five-sided. Pitchers were not confined by a rubber, allowing them to run, hop, jump, and skip before releasing the ball. The catcher was bare-handed and stood far behind the batter to return the pitch, unless runners were on base. There was one umpire, who moved to the infield when there were men on base, the better to adjudicate across the big pasture. Players wore all-woolen uniforms, though you wouldn't say they were uniform, settling mostly for the same colored sock or top jersey; gloves were for protecting the palm (and some players wore one on each hand, and some...wore none); bats were more like long clubs (some over three and a half feet long); the ball was rubber, yarn, and leather; the ballparks were made of hazardous wood, risking fire and collapse; the outfields were more likely ringed by spectators and horse carriages than walls or fences." Michael Coffey,27 Men Out: Baseball's Perfect Games. New York: Atria Books, 2010.

The teams bore such familiar names as Giants, Mets and Nationals but also oddities like Boston Beaneaters, Chicago Orphans, Brooklyn Bridegrooms, Alleghany Innocents, St. Louis Perfectos, Rochester Hop Bitters and Providence Clamdiggers.

Life for a 19th century professional baseball player was no bed of roses. Just think of being jostled about during endless train rides. And it was hard on the hands too; early baseball was a game played without gloves. Three baseball cards show Gerhardt bare handed.

Here follows a summary of the major and minor league performances of this baseball pioneer plus his team results:

1873 age of 18 Washington Nationals or Blue Legs. Beginning September 1, he served as an "extra man" on the Blue Legs. He played in 13 games as short stop and got 12 hits (including 3 doubles), scored 6 runs, batted in 9 runs for a batting average of .211, and .710 fielding percentage. In 1873 the Blue Legs won 8 and lost 31 for a seventh place finish among the nine National Association teams led by the Boston Red Stockings. Their home field, Olympics Grounds, was located at 16th Street NW (east); 17th Street NW (west); and S Street NW (south).

The full name of the league in which Gerhardt played in 1873-75 was the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players. Established in 1871, the National Association was the first professional baseball league. "Its status as a major league is in dispute. [Official] Major League Baseball and the Baseball Hall of Fame do not recognize it as a major league, but the NA comprised most of the professional clubs and the highest caliber of play then in existence. Its players, managers, and umpires are included among the 'major leaguers' who define the scope of many encyclopedias and many databases developed by SABR [Society for American Baseball Research] or Retrosheet." ("National Association of Professional Base Ball Players," Wikipedia). Baseball-Reference.com refers to "National Association (Major League)." Seven players from the National Association are listed in the National Hall of Fame (Wikipedia), including Cap Anson, Albert Spalding and George and Harry Wright. When the National League was formed in 1876, six of its eight teams came from the National Association, evidence that the NA was of major league caliber.

With his next team, Joe fared even worse:

1874 age of 19 Baltimore Canaries, Yellow Stockings or Lord Baltimores, 14 games, 19 hits, 10 runs, 6 runs batted in, .311 batting average, .750 fielding percentage. Team win-loss ratio 9-38. Canaries ended 8th out of 8 in the National Association. Venue: Newington Park (West Baltimore: Pennsylvania Avenue extended).

Next, he was third baseman for the Mutuals of New York for a full season:

1875 age of 20 New York Mutuals, 58 games, 54 hits, 29 runs, 20 RBI, .214 batting average, .813 fielding percentage. Team 30-38 win-loss ratio. Mutuals were seventh in the National Association. Venue: Union Grounds (Harrison and Marcy Avenues, Brooklyn, NY).

Playing with such weak teams must have been a tough start for Joe, but he kept going. In 1876, he was second baseman with the Louisville Grays, a National League team. The Grays were charter members of this league, which was founded February 2, 1876. Joe himself could be described as a charter member of the National League when he suited up for the Grays.

1876 age of 21 Louisville Grays, 65 games, 76 hits (2 home runs), 33 runs, 18 RBI, .260 batting average, .944 fielding percentage. Team win-loss ratio 30-36; fifth in the National League. Venue: Louisville Base Ball Park, KY.

His chance to play with a first-rate team came next year when he achieved his highest full-season batting average.

1877 age of 22 Louisville Grays, 59 games, 76 hits (1 home run), 41 runs, 35 RBI, .304 batting average, .892 fielding percentage. Team win-loss ratio of 35-25; second in NL. Venue: Louisville Base Ball Park, KY.

Unfortunately a few of the players couldn't resist throwing games, which resulted in the demise of the team. Joe had better luck in 1878 when he was second baseman with the Cincinnati Reds.

1878 age of 23 Cincinnati Red Stockings or Reds, 60 games, 77 hits, 46 runs, 28 RBI, .297 batting average, .906 fielding percentage. Team ratio 37-23; second in the National League. Venue: Avenue Grounds, Cincinnati.

However, the next year his batting average plummeted.

1879 age of 24 Cincinnati Reds, 79 games, 62 hits (of these, 12 were two baggers, 3 triples and 1 homer), 22 runs, 39 RBI, .198 batting average, .907 fielding percentage. (Joe played every infield position.) Team 43-37 win-loss ratio; fifth in NL.

In 1880 Gerhardt returned to his home town and helped his original team, the Washington Nationals, win the league championship. Did his father have a chance to watch his son play? The general died the following year; namely on August 19, 1881, at the age of 65, from the malaria he had contracted during the Civil War. Joe's mother, German immigrant Dorothea Wolff, would die in 1905. Joe's statistics for the 1880 season were as follows:

1880 age of 25 Nationals of Washington, 48 games, 206 times at bat, 42 hits (5 doubles, 3 triples), 33 runs, .204 batting average. First in National Association.

The prologue to the subsequent championship series between the National Association and the National League was as follows:

July 8-The Chicago White Stockings (today the Chicago Cubs) win their 21st consecutive game ("1880 in Baseball, Champions," Wikipedia).

July 26--Chicago is beaten by the Nationals of Washington‚ 2- 1‚ in 12 innings in an exhibition game in Springfield‚ MA (Charlton's Baseball Chronology-1880).

August 2--George Derby and the Nationals shut out Buffalo‚ 7- 0. The Nationals have a decisive lead in the three-team National Association race at this point (Charlton's Baseball Chronology-1880).

September 15-The Chicago White Stockings clinch the NL pennant with a 5-2 win over the Cincinnati Reds ("1880 in Baseball, Champions," Wikipedia).

September 29-The Polo Grounds hosts its first baseball game as the newly formed New York Metropolitans defeat the National Association champion Washington Nationals 4-2. The approximately 2,500 people attending the game are the largest crowd to see a game in New York City in several years ("1880 in Baseball, Champions," Wikipedia).

Often in financial difficulties, teams were wont to schedule champion series on their own to attract spectators. Chicago and Washington did just that. They staged an unofficial forerunner of the later World Series.

October--An ad-hoc, inter-league playoff series is held between the Washington Nationals, champions of the National Association, and the Chicago White Stockings, champions of the National League ("1880 in Baseball, Champions," Wikipedia). Chicago played their home games at Lake Front Park I.

The first game of the series is held on 9 October; it is a Chicago victory 7 to 4 over Washington. On 13 October another victory by Chicago, 4 to 2. However, Washington was the final victor in this series according to Wikipedia: "National League: Chicago White Stockings, National Association: Washington Nationals Inter-league playoff: Washington (NA) defeated Chicago (NL), 4 games to 3 (1 tie game" ("1880 in Baseball, Champions," Wikipedia).

Joe Gerhardt concluded his career as follows:

1881 age of 26 Detroit Wolverines, 80 games, 72 hits, 35 runs, 36 RBI, .242 batting average, .908 fielding percentage. Fourth in the National League with a 41-43 record. Venue: Recreation Park, Detroit, MI.

Rule Change: In 1881, the distance between the front end of the pitcher's "box" and home plate was increased to 50 feet from 45 feet.

In 1882, Gerhardt was apparently inactive. Next Gerhardt played awhile in the American Association. "The American Association (AA) was a major league that existed for 10 seasons from 1882 to 1891. During that time, it challenged the National League (NL) for dominance of professional baseball" ("American Association," Wikipedia).

1883 age of 28 Louisville Eclipse (player-manager), 78 games, 84 hits, 56 runs, 14 RBI, .263 batting average, .906 fielding percentage. Team win-loss ratio 52-45 for fifth place in the American Association.

In March 1883, he married in Cincinnati Edith M. Winkleman; they had

one child. Edith was the sister of George W. Winkleman, who was born

in 1858 in Ohio and played four games, August 4 to 9, 1883, as an

outfielder for the Eclipse. Since Joe was player-manager of the

Eclipse at this time, it is likely that he gave a tryout to his

brother-in-law. The results were not encouraging.

In March 1883, he married in Cincinnati Edith M. Winkleman; they had

one child. Edith was the sister of George W. Winkleman, who was born

in 1858 in Ohio and played four games, August 4 to 9, 1883, as an

outfielder for the Eclipse. Since Joe was player-manager of the

Eclipse at this time, it is likely that he gave a tryout to his

brother-in-law. The results were not encouraging.On July 26, Joe was forced out of action due to temporary paralysis; he recovered and played again within 2 weeks.

Venue: Eclipse Park I, Louisville, KY. This park at 28th and Elliott streets in west Louisville had a 5,000-seat grandstand, a club room where gentlemen could enjoy refreshments from local distillers, a scoreboard with the names of the players, and a tower on top of the grandstand that might have been the first sky box.

Things were sometimes helter smelter in early baseball. On Memorial Day May 30, 1883, an American Association game was played at the Polo Grounds on the New York Metropolitans portion and simultaneously a National League game was played at the Polo Grounds on the New York Gotham's field where the outfield fences backed up to one another.

1884 age of 29 Louisville Eclipse (player-manager for part of season), 106 games, 89 hits, 39 runs, 40 RBI, .220 batting average, .920 fielding percentage. Team 68-40 win-loss ratio for third place in AA. Eclipse Park I, Louisville. Rule Change: Over-hand pitching was permitted; also the Louisville Slugger bat was introduced.

Next Joe played with the New York Giants, a strong National League team that played in the original Polo Grounds (today part of Central Park), NY.

1885 age of 30 New York Giants, 112 games, 62 hits, 43 runs, 33 RBI, .155 batting average, .911 fielding percentage. Team win-loss ratio 85-27; second place in NL behind the Chicago White Stockings. Venue: Polo Grounds I, NY. Annual salary: $2,260.

1886 age of 31 New York Giants, 123 games, 81 hits, 44 runs, 40 RBI, .190 batting average, .911 fielding percentage. Team win-loss ratio 75-44; third in National League. Venue: Polo Grounds I.

1887 age of 32 New York Metropolitans, 85 games, 68 hits, 40 runs, 27 RBI, .221 batting average, .896 fielding percentage. Team win- loss ratio 44-89; seventh in the American Association. Venue: St. George Cricket Grounds, Staten Island, NY. Annual salary: $1,560.

1888 age of 33 Jersey City, NJ, Skeeters (nickname derived from the word mosquitoes) (manager). Team win-loss ratio 84-25; second in the Central League (minor).

1889 age of 34 Hartford Nutmeggers (after the nickname of the State of Connecticut) (manager). Team win-loss ratio 52-44; third place in the first Atlantic Association (minor).

Then Gerhardt returned to the big leagues.

1890 age of 35 Brooklyn Gladiators, 99 games, 75 hits, 34 runs, 40 RBI, .203 batting average. Team win-loss ratio 26-73; ninth and last in the American Association, a major league. Annual salary $3,390. Venue: Ridgewood Park II in Queens, Polo Grounds III and Long Island. The Brooklyn Gladiators folded after this first season. Gerhardt signed as a free agent with the St. Louis Browns, August 25, 1890.

1890 age of 35 St. Louis Browns (part-time player-manager). The last game he managed was on October 14. While player-manager, the Brown's had a 20-16 win-loss ratio. Gerhard's personal totals were 37 games, 32 hits (1 home run), 15 runs, 11 RBI, .256 batting average, .947 fielding percentage. Tearn win-loss ratio 77-58; third in the American Association. Venue: St. Louis: Sportsman's Park I.

1891 age of 36 Louisville Colonels (successors of the Louisville Eclipse), 2 games, six times at bat and one base on balls. Joe's last game in the majors was on April 29, 1891. Venue: Eclipse Park.

From 1873 to 1891, Joe collected 981 hits (7 home runs), 526 runs and 382 runs batted in for a major league batting average of .227.

Gerhardt had been a player-manager in 1883 and 1884 for the Louisville Eclipse and in 1890 for the St. Louis Browns. In 1888, he was manager for the minor league New Jersey Skeeters and in 1889 for the Hartford, CN, Nutmeggers. Then he would lead Albany to first place.

1891 age of 36 Albany, NY, Senators (co-manager), 106 games, 83 hits (14 two-baggers, 5 three-baggers, 1 home run), 55 runs, .240 batting average. First place in Eastern Association (minor league).

1892 age of 37 Albany, NY, Senators (sole manager), 4 games, 13 times at bat, 1 hit (a two bagger), 2 runs, .077 batting average. First place in Eastern League (minor league).

1893 age of 38 Albany, NY, Senators ( sole manager), 4 games, 14 times at bat, 1 hit, 3 runs, .071 batting average. First place in Eastern League.

So we see Joe putting on a creditable batting performance with the 1891 Albany Senators, which he helped lead to first place. He also led the 1892 and 1893 Senators to first place; however, he got only 1 hit in 4 games each year. He was now almost 40 and having spent 20 years on the diamond, his playing days were drawing to a close.

In summary: Joe had only a moderate batting capability. His career batting average during his 16 years in the majors stood at .227. The year 1877 was the only complete season where he posted a batting average over .300, and 1890 was the only time he managed over 100 hits in a season. But he did have some decent years with the bat: In 1883, he hit 9 triples, and the next year he hit 8. (We have to keep in mind; this was the era of the "dead" ball, when everyone's batting averages were lower.) In the Nineteenth Century the "same ball would be used throughout the game, and foul balls would be thrown back on the field and reused. The ball would only be replaced if it started to unravel. As games progressed, the ball would become increasingly dirty and worn, making it difficult to see and its movement erratic" ("Live-ball era," Wikipedia).

While a moderate hitter, Gerhardt nevertheless played 1,125 games in the majors on the strength of his fielding. He led his league in second basemen assists twice. At second base for the NY Giants in 1885, he executed a triple play (three outs in one play) against Providence with Roger Connor as the first baseman. Bare-handed fielding was of course much more difficult than fielding with the modern deep-pocket gloves.

Concluding his baseball career in New York State, "Move Up Joe" decided to settle there. He worked as a hotelman at Liberty House in Liberty, NY, and at the Palm Hotel in Montecello, NY. During the last three years of his life, he was employed at the N. D. Mills Cigar Store in Middletown, New York. Middletown is west of West Point.

"On March 3, 1922, while returning from lunch at his residence at 23 Mulberry Street, he was stricken by a fatal heart attack. Newspaper obituaries reported that Joe was well-known and had thrilled many residents and fans with stories of his experiences during his baseball career. Following a memorial service in Middletown, his funeral took place in Washington, DC, with interment in the family plot at Prospect Hill Cemetery" (Jean Bischof Grabill, The Families of Prospect Hill: Prospect Hill Cemetery of Washington, D.C., 1858- 1997. Publisher: Prospect Hill Cemetery, 2201 North Capitol Street, Washington, D.C. 20002-1103).

"Move Up Joe" Gerhardt died in New York's Hudson Valley at Middletown, Orange County, in 1922 at the age of 67. He is buried in the District of Columbia where he was born, near his father, General Joseph Peter Gerhardt.

by Gary (Gerhardt) Carl Grassl.

back to top

With the help of the underground, he was able to escape, eventually coming to America and Washington, DC in 1854. Once he became settled here he quickly changed his name to Henry Walther. Taking any job he could get, he finally saved enough to build a small frame house. Wanting to become totally American, he burned his coat of arms in the yard of this house.

When the Civil War broke out, Henry joined the 8th Battalion, DC Volunteers. Eventually he fought with and helped guard General Grant. One cold, snowy morning he was guarding the General's tent when the General took a slug of whiskey to warm himself. Walther said. “I could do with a bit of that myself, General.” Grant granted his wish.

The night Lincoln was assassinated, Walther was on guard duty on the aqueduct bridge in Georgetown.

After the war Walther opened a paint store. He also did fresco art work in the Capitol with Bromedi; the flowers in the come are examples of his work.

back to top

Musical Director of the Washington Saengerbund

from September 1896 until April 1910

|

|

|

Henry Xander early on was destined to take over his father’s growing wine business but at the age of nine he showed signs of a budding musician by displaying his talent at the piano. He started with piano lessons while attending public school in Washington, DC and was encouraged to continue his musical studies. By 1880 he had progressed to the point that his family decided to send him to Stuttgart, Germany where he would study piano and composition at the Conservatory of Music. Jean Crabill, a historian for Prospect Hill Cemetery, wrote that Henry remained in Stuttgart for five years. During three of these years he played with the Oratorio Society and participated in conservatory concerts. On one occasion he performed an organ sonata that he had composed and was highly praised by music critics.

In 1885, upon completion of his studies in Stuttgart, Henry went to Berlin to study for one year and then continued further studies in Paris, remaining there for another year. He returned to Washington in 1887 with his mother Caroline and his sister Minnie who had traveled to Europe for a vacation and accompanied him back home.

When Henry Xander appeared on the local scene he became keenly aware of Washington’s lack of musical culture. He was quoted as saying “I often wonder what the foreign diplomats stationed in this beautiful city think of the capital of a great and rich country not having its own opera, symphony orchestra, oratorio society and chamber music societies. Cities in continental Europe of 50,000 inhabitants have them. Small towns all over the country have given annual musical festivals, some of them for over a half century. Why can’t we do likewise in the National Capital?”

He began to perform in public concerts as accompanist and solo pianist, and established his own local studio to give musical instructions in piano and theory. In February 1888 two concerts by the Washington Symphony Orchestra were performed at the National Theater with conductor John Philip Sousa, the famous composer and Marine Band leader, with Henry Xander as accompanist. Also in 1888 a new Chamber Music Society was formed featuring Henry Xander as the solo pianist with concerts at the Congregational Church in Washington, DC. A music critic wrote “Mr. Henry Xander played several numbers on the piano with brilliancy.”

On Oct. 27, 1889 a Grand Sacred Concert for the benefit of the German Orphan Asylum was given at the National Theater by the Washington Saengerbund under the direction of Professor William Waldecker, and assisted by Henry Xander. This appears to be the first mention of Xander’s name performing in public with the Washington Saengerbund. By 1894 the Washington Saengerbund had acquired its own property at 314 C street, northwest and turned it into a clubhouse. The multi-story structure included a lavish parlor with a grand piano, a restaurant with bar, clubrooms for rehearsals, a musical library, and later a bowling alley in the basement. There was also an annex in the back of the property which in 1896 was renovated and converted into a concert hall and ballroom with seating capacity for 500 guests. Weekly entertainments were offered throughout the year.

At a meeting of the Washington Saengerbund on July 25, 1896 it was announced that Mr. Henry Xander had agreed to become the new musical director of the Washington Saengerbund to succeed Prof. Waldecker. By September of that year a newspaper report states that “Mr. Henry Xander, the new musical director of the Saengerbund, is already making his powers felt. The singing of the Bund on the occasion of the visit of the New York Beethoven Society showed the effect of Mr. Xander’s careful and capable training.” On Dec. 7, 1896 the Saengerbund’s first public concert under Henry Xander was given at Columbia Theater and the critics wrote: “… The entire concert was under the direction of Mr. Henry Xander, the musical director of the Saengerbund, who appeared before the public for the first time, and demonstrated his varied musical abilities in the most satisfactory manner. Under his direction the Saengerbund cannot fail to improve in its vocal work, and its concerts will surpass even their former high standard.”

From then on the quality of the Washington Saengerbund continued to elevate to an ever higher level. The chorus consisted of 75 high quality singers, and concerts featured instrumental and vocal guest performers from Washington, DC as well as other cities. Throughout the year the clubhouse on C street became a meeting place for their more than 900 members and families with musical and theatrical entertainments. Each season two public concerts were presented at local concert halls, most prominently at the National Theater in Washington, DC. Tickets readily sold out to enthusiastic audiences.

At its fiftieth anniversary in 1901 the Saengerbund began a three-day celebration with a grand concert at the National Theater. The Saengerbund was represented by fifty-three voices, reinforced by an orchestra of forty instruments under the leadership of Mr. Henry Xander. Among the guest performers at the concert were the noted Austrian violinist Franz Wilczek, and Mme. Charlotte Maconda, the distinguished soprano from the Metropolitan Opera in New York. Every seat in the theater was occupied long before the beginning of the concert and many persons appeared content with standing room. Among the many prominent guests were the German ambassador and his wife.

By 1910 Henry Xander had been the successful musical director of the Washington Saengerbund for fourteen years when he announced that he “was compelled to resign as conductor due to business reasons.” Henry and his sister Minnie had taken over the operation of the Christian Xander Liquor and Wine business after their father Christian

|

|

|

After his retirement as Saengerbund musical director he took long vacations each summer with visits to the New York Metropolitan Opera from where he regularly sent reports. In his later years he lived at the Shoreham Hotel where he remained until he died in September 1953 at the age of 88 after a two-month illness. The Washington Journal in an obituary said “With him dies a piece of German-American music life, but the Saengerbund is still here, more than 100 years old.”

by Al (Alwin) Wenzel - May 2017

back to top

Some touched the presidency in different ways:

Frederick Spiess was a tailor for President Lincoln.

Christian Meininger made boots and shoes for Theodore Roosevelt. A friendship developed between the two men and they were known to go bike riding together.

August J. Voehl was General Grant's bootmaker.

William ("Uncle Billy") Wagner, who owned a sporting goods store on Pennsylvania Avenue, SE, near the Capitol, had Presidents Cleveland and Roosevelt as regular customers. It was said that President Cleveland would shoot nothing but shotgun shells loaded by "Uncle Billy", and on several occasions sent for him to ask his advice about guns and ammunition, as did Theodore Roosevelt.

Others were involved in the life of the city itself:

August Grass was a gifted cabinetmaker responsible for the woodworking in many fine Washington homes, including the Heurich Mansion.

John Frederick Herrmann opened Washington's first bottling company and eventually became known as Washington's "ginger ale man.".

Jeweler William Kettler was responsible for keeping the mechanical clock in the tower of the Old Post Office in good repair.

Horticulturist Herman Zoellner landscaped Dumbarton Oaks and the Naval Observatory.

Refugee August William Henry von Walt Herr was so happy to be in the United States that after "Americanizing" his name to Henry Walther, he took his coat of arms and burned it in his back yard on L Street, NW. At first accepting any job offered to him, he once worked as a bartender in Alexandria, commuting to and from this job by swimming across the Potomac. He later did fresco art work at the Heurich Mansion and with Bromedi at the Capitol.

Retired shoemaker Christian Feige took a job as a musician at the Knickerbocker Theater. He died while playing with the orchestra when the theater roof collapsed during the blizzard of 1922.

At one time a brickyard employee, John Hensel, using non- sellable rejects, built his home on the site where Union Station now stands.

Peter Wittstatt came to America to accept an invitation to play in the United States Naval Academy's band.

Dr. Amelia Erbach was the second woman admitted to the District of Columbia's medical society. She had a private practice for women and children.

Home back to top